Faith And The intifada

Rosemary Radford Ruether

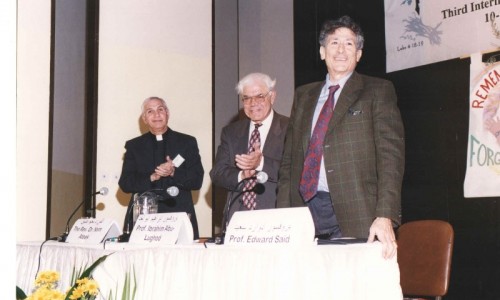

This book represents, in part, papers that were given at the First International Symposium on Palestinian Liberation Theology at Tantur, between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, during March 10-17, 1990.

The conference itself was two years in the planning, and several workshops were held around Israel and Occupied Palestine to prepare for it. The conference was not an end in itself, but was seen as part of a process by which Palestinian Christians across all historical traditions established a conversation about their own theology, contextualized in their national struggle for liberation.

As father Naim Ateek makes clear in his opening remarks, a Palestinian theology of liberation had become necessary, not simply because Palestinians were engaged in a struggle for national liberation, for this had been the case since the time of the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration after World War I. But this struggle was seen as a secular struggle, a struggle against colonialism and for a democratic state where Palestinians of all religions had equal civil rights.

A specifically theological reflection had become necessary because Israeli and Diaspora Jews and also Western Christians were evoking the Bible and theological themes from the Jewish and Christian religions to claim a divinely-mandated right of the Jews to the land. After the 1967 war and the occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza, these religious claims became more extreme and were applied to these occupied territories. Palestinian rights were disregarded altogether by these religious Zionists.

Palestinian Christians had a particular need to formulate a reply to these biblical and theological claims, since such claims came from the scripture they held in common with these opponents. This misuse of the Jewish and Christian scriptures by religious Zionism also left the impression in the minds of many Muslims in the Middle East that these were representative Christian teachings, and thus Middle Eastern Christians themselves were implicated in such teachings. Middle Eastern Christians also had to take the lead in protesting to the Western Christian churches the use of the Bible and the name of God to promote injustice.

It was no easy task to develop a common theological conversation among Palestinian Christians. The Christian community in the Holy Land has been tragically victimized by the very veneration in which this region has been held by Christians around the world. Every historical Christian tradition, from Old Catholics and Orthodox to Roman Catholics to every form of Protestantism, has aspired to have its titular community in Jerusalem and in the Holy land. The indigenous churches have been continually fragmented by this ecclesiastical imperialism, dominated by foreign clergy and funding.

Indigenous Christians, particularly in the last forty years, have had an increasingly difficult time maintaining their presence in their own land. The pressures to emigrate from the Israelis have particularly affected Palestinian Christians with their greater opportunities for education and ties with the West. Thus, as Don Wagner shows in his chapter in this book, there is real danger that Palestinian indigenous Christianity will dwindle to the point that only dead stones. But not a living church, will testify to their historic presence in the land of the birth of Jesus.

This fragmentation across all the historical divisions of church history, together with pressures to emigrate, made the task of creating a base for a Palestinian theology of liberation especially challenging. Yet this book also testifies to the success of that process. As one reads the chapters of this book, one has a sense of a common Arab Palestinian Christian voice. The fact that the authors range across denominations-Mennonite, Quaker, Lutheran and Presbyterian, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Melkite and Greek Orthodox- is discovered only by reading the brief biographies of the contributors. In the actual conference both the Greek Catholic seminary choir and the Armenian church choir provided music for the worship services.

Thus one might say the first task of this conversation on Palestinian liberation theology was to generate a common sense of being the church of Palestine, the indigenous Palestinian local church. As Geries Khoury emphasizes in his chapter, Palestinians must develop an ecclesiology of the local church to overcome this historic fragmentation and to speak with one voice as Palestinian Christians. It is only in that context that it then becomes possible to discuss a Palestinian theology of liberation that responds to and expresses the national struggle for liberation. Here Palestinian people across the three monotheistic faiths, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim.

This conference hoped not only to bring together Palestinian Christians, but also to assemble international representatives of liberation theologies around the world to reflect with them and to learn from them and to learn from them. Palestinians felt the need to learn from the experiences that Latin Americans, Asians, and Africans, had already had in developing indigenous liberation theologies in the context of their historical cultures and struggles for justice. Palestinians were also aware that many liberation theologians around the world were oblivious to Palestinian Christians and to the Palestinian struggle. They thoughtlessly used themes of “exodus” and “promised land” with little sense of the negative use of such biblical themes to oppress and colonize the Palestinians.

Thus the Palestinians also hoped to consciencticize the world community of liberation theologians, to make them aware of the negative underside of many biblical themes, when these are used in an exclusivist, ethnocentric sense as a theology of conquest.

Invitations went out to liberation theologians around the world, to Latin America, North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Unfortunately, most liberation theologians were not prepared to put the Palestinian issue on their agenda. No Latin American theologian came, although many showed initial interest. Africa and Asia were better represented with Malusi Mpumlwana from South Africa, Emmanuel Kandusi from Zimbabwe, Shirley Wijedinghe from Sri Lanka, and Myrna Arceo from the Philippines.

(Unfortunately, of these four only Myrna Arceo sent a paper for the book.)

Europe was represented only by Ireland in the person of Dr. Ann Louise Gilligan. Thus in this book the section on international response is much more North American than was the original hope.

However, the first purpose of the conference, which was to gather a representative dialogue among Palestinian Christians, was well expressed at the conference and even more so in this book, since several Palestinian Christian leaders, such as Father Elias Chacour and canon Riah Abu El-Assal, who had participated in the planning of the conference, were not able to make the actual conference itself. However, they contributed papers, which are part of this publication.

As is the case with liberation theology generally, Palestinian liberation theology is reflection on praxis. Therefore it begins by analysing the situation of oppression and the struggle for liberation. For Palestinians this situation of oppression is Israeli occupation, and the struggle for liberation is the Intifada, the organized uprising against occupation which has been conducted with great suffering, primarily as a nonviolent struggle, since December 1987. Thus many of the articles in this book take the form of analysing this situation of struggle.

Dr. Hanan Ashrawi and Dr. Salim Tamari, both of Bir Zeit University, provide political and sociological analyses. Dr. Jad Isaac of Bethlehem University delineates the struggle for the land and the maintenance of a Palestinian agriculture, the crucial basis of Palestinian economic and cultural survival. Sameeh Ghnadreh contributed a discussion of the distinct social and political situation of the Palestinians within Israel, primarily in the Galilee, who are Israeli citizens, but suffer under second-class citizenship and continual encroachment upon their remaining land. These are the remnant of that Palestinian community that was driven out during the 1948 war when the Israelis pushed out a million Palestinians and destroyed some 450 villages, confiscating more than 80 percent of the land that had been held by Palestinians.

Many of the other papers in this collection are primarily sociological in nature. They represent the voice of the Palestinian experience, articulating its sufferings and also hopes that the intifada has brought to a silenced people the world seemed to have relegated to the dustbin. It is in this context of the articulation of the Palestinian experience of struggle that these authors then dare to venture a theological word, a word about the connection between faith and the intifada, and also a word about what the role of a Palestinian church must become

Although the sufferings of Palestinians after two and a half years of organized uprising were extreme in March 1990, this situation has significantly worsened in the ensuing eighteen months, particularly during the Gulf War of January to March 1991 and its aftermath. The Israeli government and military took the opportunity afforded by world sympathy and diversion of attention during this war to age an all-out economic was against the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories.

A million and a half people in the occupied Territories were kept under continual curfew for six to nine weeks. The Palestinian economy was devastated. Crops and animals died because Palestinians were not allowed out of their homes to tend them. Unemployment soared to 50 percent, the medical and education situation deteriorated further, and many Palestinians, particularly in Gaza and in the refugee camps, faced starvation. After the war was over it was evident that the Israeli government did not intend to return even to the conditions before the war, but rather to impose travel restrictions and continual curfews that would make daily life for Palestinians close to impossible. At the same time there was a new stage of land confiscation, the rapid building of new settlements and expansion of old ones, so that now some 60 percent of the West Bank and 40 percent of Gaza have been confiscated, not to mention the almost total control of water.

Clearly the Israeli government wishes to create so many “facts on the ground “

That any political settlement that would trade land for peace would become impossible. Nor were the Palestinian communities within Israel exempt from this pressure. The galilee also saw new expansion of Jewish settlements, squeezing still further the diminished land available to the thousands of immigrants from the soviet union were being rushed into Israel to provide a demographic base for the take-over of all Palestine by Israeli settlement.

Soviet immigrants also were victimized in this process because many had been partly coerced to come to Israel by deliberate blocking of their opportunities to immigrate to other countries, particularly to the United States, which many would have preferred. Many of the new immigrants found that the planning for their arrival was so poor that they were both homeless and jobless in Israel. Israeli newspaper reported numerous Soviet women being sent into streets as prostitutes to make a living3. Despite feeble protests, it is primarily American money that continues to subsidize this Zionist project of squeezing out Palestinians and replacing them with Jews, a process in which Palestinians are the first victims but many of the Jewish immigrants are unjustly treated as well.

This book on Palestinian theology is thus offered to the American and English reading public at a critical time, a time which, as Jewish theologian Marc Ellis has warned, may see the end of the Palestinian community in historic Palestine. This will go down in history as one of the great crimes of Western colonialism, along with the extermination of indigenous people in so many other parts of the world. It is a particularly egregious crime because it has been one in which Western Christians have collaborated with Jews, and both have exploited the memory of past injustice and the mandates of religious faith to cover it up and carry it out. Yet there is still time for repentance. There is still time for an Israeli community of conscience to grow in Israel. During the intifada thousands of Israeli Jews crossed the “Green line” that divided Israel from the occupied Territories, got to know Palestinian people for the first time, and entered into movements of solidarity. The Israeli peace Movement began to be a movement with Palestinians, rather than simply a movement that referred to Palestinians in absentia.

As Michel Warschawski of the Alternative Information Center has made clear, this new stage of the Israeli Peace Movement faded during the Gulf war primarily because it was not deep enough. It was still based primarily on seeing the Palestinian as enemy rather than as a neighbour whom one wishes to live with as a fellow human being. Yet the seeds were planted, and it is very much up to the world community to help support and nurture these hopeful beginnings of a new community of Palestinians and Israeli Jews who have determined to create the conditions of authentic justice and peace.

These conditions begin when the Palestinians are recognized not as stereotypical enemy, not simply as victims, but as a people with great heart. This people has extended the hand of friendship to Israeli Jews and is ready to find basis of genuine justice and peace, based on an affirmation of the rights of both people to share the land they both love.

But the Palestinians – Muslim and Christian- and the Israeli peace community cannot create this change by themselves. The world community must finally say “Yesh Gevul” (enough”) to subsidizing land confiscation, settlements, and the destruction of the Palestinian community, and yes to an international peace conference under the United Nations. The chapters of this book represent this Palestinian hand of peace with justice extended to the world. The time for an adequate response has grown very short!